A discussion on Reddit a little while ago pointed out a common mechanic (or mechanism, if you prefer) that many games use, but which lacks a name. I love this mechanic, and I call it the crescendo mechanic. Once I started looking for it, I saw it in more places than I expected.

Crescendo is an Italian word meaning “growing” and it usually shows up in music to tell the musician to gradually get louder. The long “greater than” sign that appears below the music staff in the image above is the crescendo symbol, and it is telling the reader to go from “mezzo forte” (medium loud) to “forte” (loud) over the course of a few notes.

In board games, the crescendo mechanic means that something the players could choose gets bigger or more valuable the longer it goes unchosen. If you pass over it, some resources or points get added to it so that it becomes more attractive to choose in the future.

Examples of crescendo mechanics

No Thanks: If a player doesn’t want to take the card, they must put a chip on it. The card keeps gathering chips until someone agrees to take it, at which point they get to keep the chips.

Agricola: Certain resource collection spaces get more and more resources on them with each passing turn, until a player eventually spends an action to take all of them.

Puerto Rico: Every role that does not get selected in a round gets a coin on it. Whenever a player takes a role, they get all of the coins that have accumulated on it.

Small World: If you don’t want a particular race/class combination, you can put a coin on it to pass over it to move on to the next one. Whenever a race/class combo is taken by a player, that player gets the coins on it. I’ll note that Daniel Solis talked about this specific type of crescendo mechanic in 2014 as “pay to pick.”

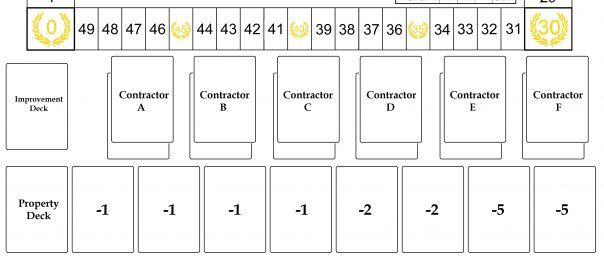

Alchemy Bazaar: The longer a shop has gone unchosen, the more valuable the goods it will pay to the player who eventually chooses it (liquid, then metal, then gem).

Why Crescendo is a great mechanic

There are several reasons that I love the crescendo mechanic, reasons that explain why it shows up so many places.

Feeling of building. Players love to feel like they are building something in a game. With the crescendo mechanic, you get some of that building feeling as a choice gets better and better. And it can lead to memorable moments: “Wow, I can’t believe you let me get nine wood from that spot in Agricola!”

Press your luck. In many games with crescendo elements, you might be willing to take the choice at its current value, but you might decide to “let it ride” and hope that you can take it later, when it’s even more valuable. This adds some great tension to the game and gets the players to judge one another – are you going to take this if I let it get more valuable, or do you want something else even more?

Automatic balancing. Figuring out exactly the right cost or reward for every game element can be extremely difficult for a game designer. The crescendo mechanic lets the designer put choices in front of the players at a low value and let the players decide when the choice is valuable enough to take.

Rewards skill. Crescendo is a very low-luck mechanic. A player who is better at figuring out what one choice is worth relative to another is going to do very well in games with crescendo elements. It’s a bit of a “shopping” mechanic: How good does the item have to be before it’s a good deal for the price? This gives players a great deal of control over their fortunes.

Other implementations?

I have a feeling that crescendo is a mechanic that shows up in subtle ways in all sorts of games. Does a drafting game where your first set of cards might come back to you have a bit of a crescendo element to it (take this good card now, or take a different good card plus the original one if it comes back)? Are there games where players choose where to crescendo, making only one possible choice among many more valuable when they choose something else? How else might crescendo be used in the future?

I’d love to hear about other interesting uses of crescendo in games. Definitely let me know if you’ve seen some good ones, either here or on Twitter.

Michael Iachini, @ClayCrucible on Twitter