I mentioned at the beginning of the year that my wife Barbara and I completed the 365 Challenge in 2016, in which we recorded 365 board game plays over the course of the year (100 different games in total). That was fun, but we decided to go in a different direction for 2017, the 10×10 Challenge (10 by 10).

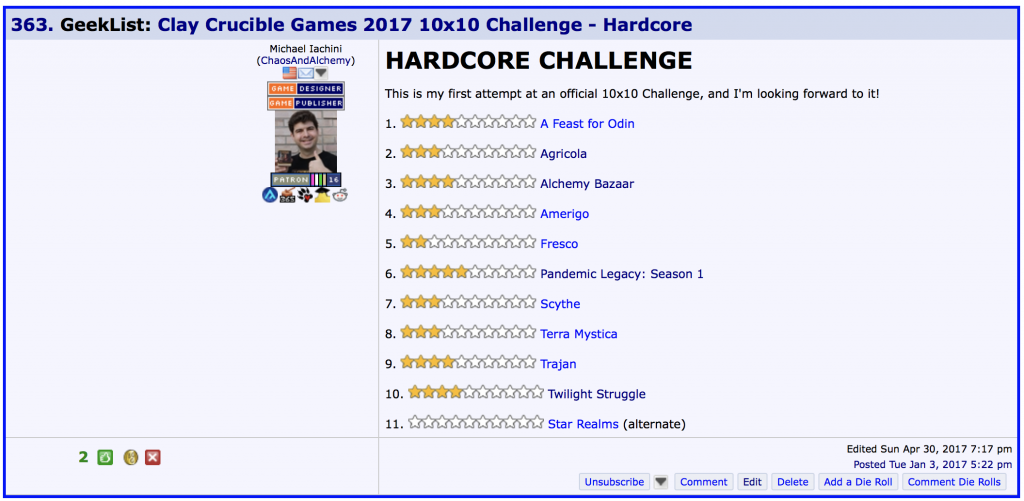

The particular challenge we’ve adopted is what’s known on BoardGameGeek as a “hardcore” challenge. We picked 10 different games at the beginning of the year, and we set a goal for ourselves to play each of them at least 10 times over the course of the year. We’re approaching the rules as follows:

- Only plays after we officially set up the challenge on BoardGameGeek count (we set it up on January 3, by which time we had already played one of the games twice – but those plays don’t count).

- Only plays with the actual, physical board game itself count. We don’t count any plays of apps or other virtual or online implementations of these games (note that these can be counted for BGG, but we’re not counting them).

- We’re only counting games that the two of us play together. So, if I play with other friends but not Barbara, I don’t count that.

- That said, it’s fine if we have more than just the two of us playing.

- Only completed games count.

With those parameters, we picked our list of 10 games at the beginning of the year based partly on games we just love and games that we don’t yet know very well and that we want to explore more. We didn’t put a ton of thought into the list – we just looked at our collection and picked some games. All of them are pretty meaty – we didn’t pick any fillers. But frankly, that’s because we like playing pretty substantial games together more than we enjoy most fillers.

The list

Our choices are as follows:

A Feast for Odin: We acquired this in December 2016, and we played it nine times in that month, plus two more plays at the beginning of January before setting up the 10×10 Challenge. We like it a lot, so we knew we would want to play it at least 10 more times.

Agricola: Our second Uwe Rosenberg-designed game on the list, Agricola is our favorite game of all time. When we first got it in 2007 or 2008 (before I was on BGG, so before I was logging plays), we played it literally at least once a day for months. We loved Agricola so much that some friends made us custom animals out of Sculpey (this was before the game came with animeeples). Definitely one to play a bunch in 2017!

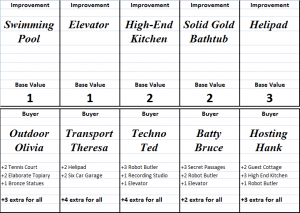

Alchemy Bazaar: I put this Michael Iachini design on the list (yes, my own game) in part because I knew I would be playtesting it during the early part of the year, and in part because I thought there might be a chance the published version would be coming out during the year. I don’t think that latter part is going to happen, but I still have a nice prototype that I want to keep playing and testing.

Amerigo: A super-fun Stefan Feld design, and the first of two games on this list that we hadn’t actually played yet when we made the list. Yes, sight unseen (well, box unopened), we put this on the 10×10 so that we would get it played. Happily, we love it.

Fresco: This is a game we’ve had for a long time, really enjoyed when we first got it, and then just haven’t played at all in years. We put Fresco on the 10×10 as an excuse to just get it back to the table. We didn’t realize when we added it to the list how odd the two-player rules are, so this is one we tend to grab more often when we have more players.

Pandemic Legacy: We were a few months into the campaign for Season 1 at the beginning of the year, and we knew we wanted to finish the campaign. There’s a chance we will finish before we get our 10th play in 2017, in which case I guess we’ll just have to play December some extra times, or else count Season 2 plays or something.

Scythe: This is the second game that we put on the 10×10 list without having actually played it beforehand. I had just heard so many great things about Scythe, and I’ve so thoroughly enjoyed all of Jaime Stegmaier’s previous publications that I felt confident we would want to play a lot of Scythe.

Terra Mystica: I think this is probably our number two most favorite game of all time (behind Agricola), so it was an easy inclusion on this list.

Trajan: We discovered Trajan at BGG Con 2016, and we were just so enamoured of it right away. It had to go on the list.

Twilight Struggle: Barbara was the one who said we should include this one, which surprised me. We played it a bunch previously, and while we both like it, Barbara tends to find it very stressful. It’s also the longest play-time for two players of all the games on the list. But hey, she picked it, and that’s cool with me!

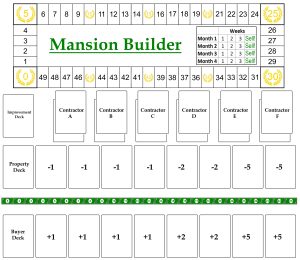

Status update

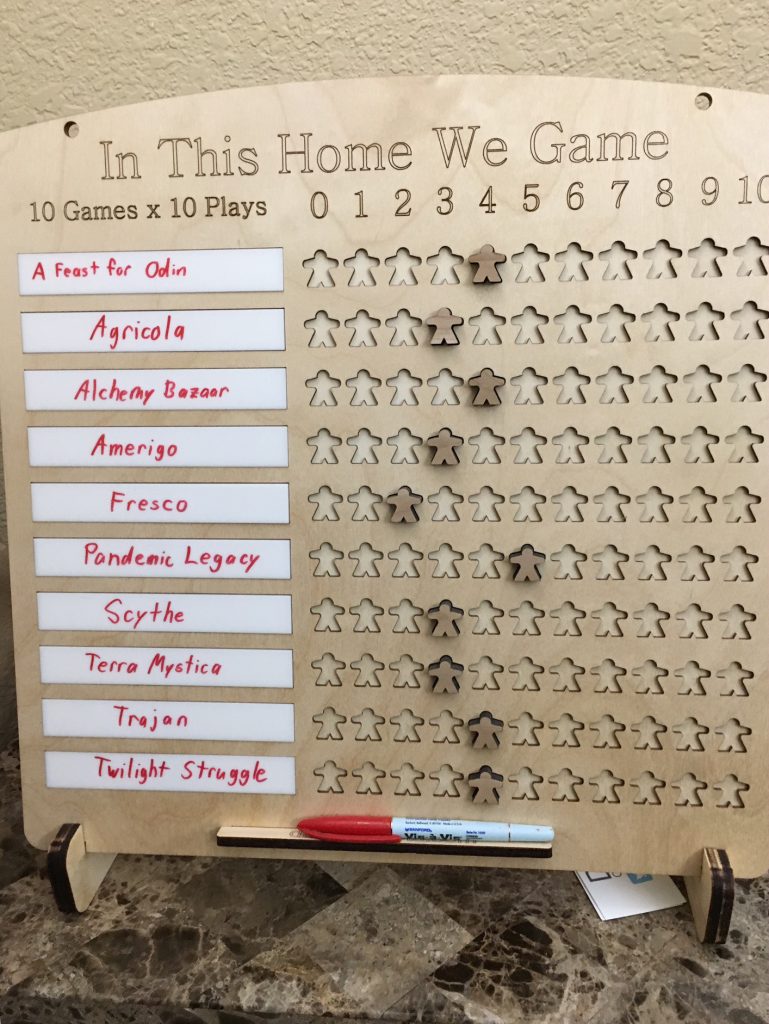

So, how are we doing as of the end of April? Well, we’re a third of the way into the year, and we are just over a third of the way through the challenge. We’ve logged 35 out of the 100 plays that we need to get.

Every game has been played at least twice (Fresco being the only one at two so far). Only one game has been played five times (Pandemic Legacy). The rest are all at three or four plays.

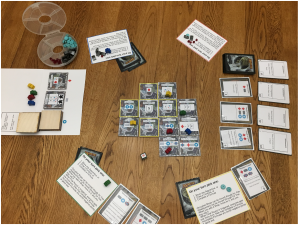

I’m logging my plays using the excellent BG Stats app for the iPhone, which now keeps track of challenges as well. I’m updating the BGG geeklist for the challenge as I go. And I also splurged and got a physical 10×10 Challenge tracker board from the excellent Daft Concepts Etsy shop. Amazingly, my cats haven’t sent the meeples flying yet (yeah, “yet” is right).

I’ll check in a couple more times over the course of the year, but I feel pretty good about our pace on this challenge! Are you doing any challenges this year? How are they going so far?